On 20 July 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to land on Earth’s only natural satellite, fulfilling half of President Kennedy’s 1961 call to get humans safely to the Moon and back by the end of the decade. How was the NRO involved in fulfilling the other half by getting NASA’s astronauts safely back to Earth?

In May 1961, President John F. Kennedy stood before Congress and proclaimed that the US should “commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth.” The initial reaction to Kennedy’s speech was tepid at best, and initially, more than half of all Americans were against the idea, citing the huge cost it would require. But Kennedy continued to champion the issue, and after his assassination in 1963, the nation adopted the challenge as a tribute to the fallen president.

At 20:17 UTC on 20 July 1969, Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the Moon (crewmember Michael Collins remained in orbit in the command module Columbia), fulfilling the first part of President Kennedy’s challenge. Six and a half hours later, Neil Armstrong opened the hatch of the lunar module Eagle, climbed down a ladder, stepped onto the Moon, and uttered his famous phrase, “That’s one small step for Man, one giant leap for Mankind.” A special video camera attached to the outside of the Eagle transmitted a TV picture of Armstrong stepping onto the Moon back to Earth, where it was viewed live by an estimated 650 million people, about one-sixth of the entire world’s population!

Armstrong and Aldrin spent just under one day on the Moon reporting on conditions, taking pictures, collecting samples, and sleeping. The next day, they returned to orbit to rendezvous with Collins in the Columbia and begin their return trip to Earth.

Meanwhile, back on Earth, Captain Hank Brandli was an Air Force meteorologist assigned to the NRO in Hawaii. He used data from the NRO’s Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) to estimate weather over drop zones in the Pacific Ocean used by the Air Force’s 6594th Test Group (the “Star Catchers”) to recover Corona film buckets and to ensure film drops occurred only on days with good weather over those drop zones. He could accurately estimate weather over the drop zones up to five days in advance -- an unheard of capability in the late 1960s.

As the Apollo 11 crew started their journey back to Earth, Capt Brandli had evidence from the DMSP satellite that told him a major tropical storm would be over the spot in the Pacific Ocean where the astronauts were scheduled to splash down on 24 July. If that happened, the parachute used by the astronauts would be ripped to shreds, their capsule would plummet into the ocean, and the astronauts would be killed on contact—not exactly the ending for their historic mission that NASA was envisioning.

Brandli knew he had to act, but there was a huge problem -- the Corona program, and the DMSP’s relationship to it, was so highly classified, the Star Catchers’ Group commander was the only other person in the Group cleared for both programs, and nobody at NASA was cleared for either.

With just 72 hours to change history, Brandli discovered that the U.S. Navy was in charge of forecasting weather for NASA. So Brandli contacted the DoD chief weather officer, Navy Captain Willard (Sam) Houston, Jr., at the Fleet Weather Center in Pearl Harbor. Although Houston was not cleared for the Corona program, he was cleared for the DMSP. Brandli showed him the photos and convinced him of the danger. Now all Houston had to do was convince Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, the commander of the naval forces tasked with the Apollo 11 recovery -- all without being able to tell him where his information was coming from because RADM Davis was not cleared for the DMSP.

Due to the extremely short timeline, RADM Davis had to reroute the entire USS Hornet task force to a new splashdown area 215 nautical miles to the northeast before he received official orders to do so, a career-ending decision if he was wrong, especially since President Richard Nixon was scheduled to fly to the Hornet to greet the returning astronauts. He also had to convince NASA to alter its flight plan so their recovery capsule landed in the right area.

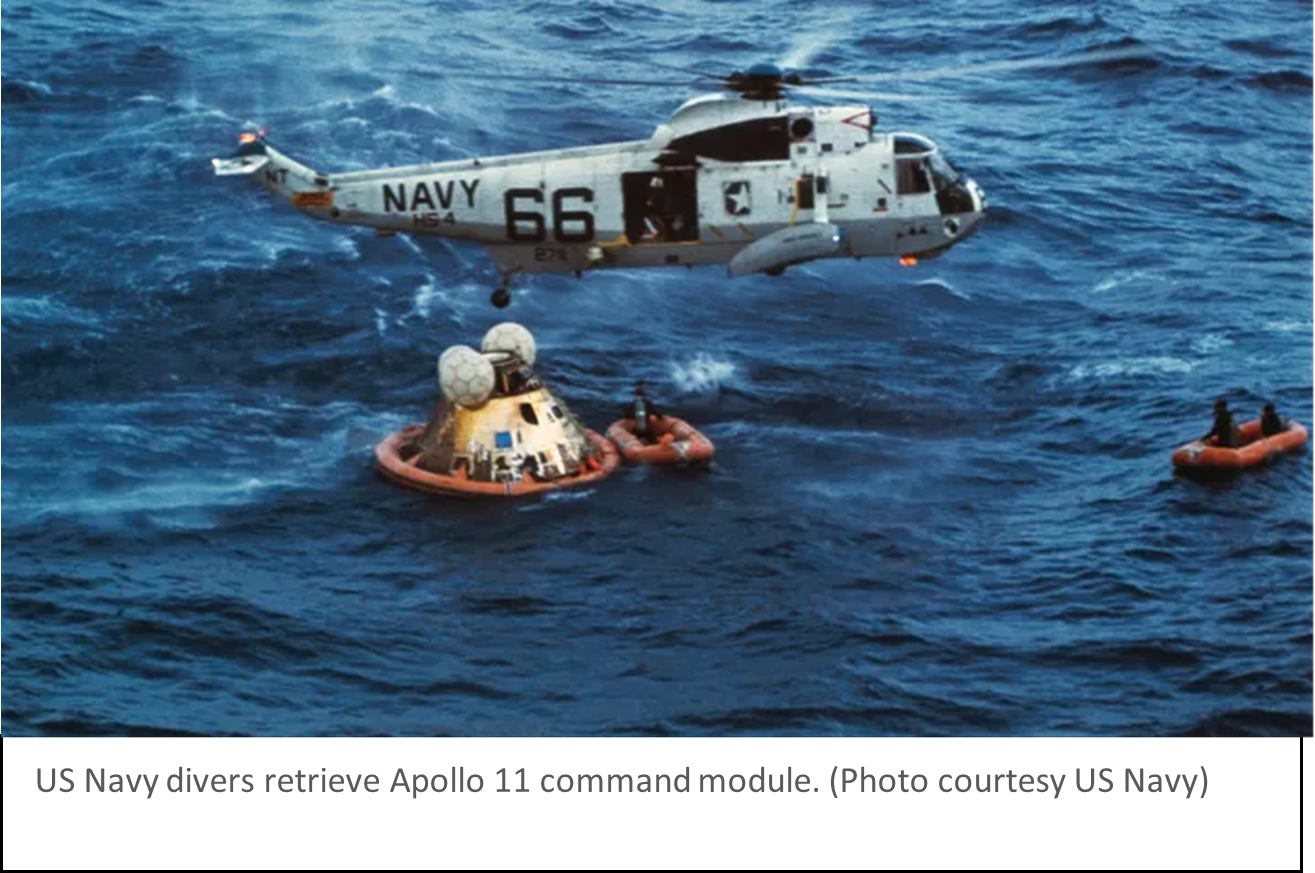

As it turned out, Capt Brandli’s forecast was spot-on, and the astronauts splashed down in nice calm seas to the relief of everyone, while weather reconnaissance aircraft flying to the previous planned landing spot reported severe thunderstorms in the area. For their efforts, Capt Houston received a Navy Commendation medal, and Capt Brandli received a visit from DNRO John McLucas and DDNRO Robert Naka, who congratulated him for his impressive work and extraordinary effort.

Because of the classified nature of the information, Capt Houston could not talk about the medal ribbon he wore on his chest, and neither man could talk about their efforts to save Apollo 11, until Corona was declassified in 1995.